Introduction: This Interview between River Hunt & Cyril Helnwein, took place on the 18th September 2009, and forms part of my ‘Interviews with Artists’ Series. It covers a wide-range of subject matter, including early influences, his father Gottfried Helnwein, detailed discussions of his photography and exhibitions, the impact of digital art and the Internet, as well as art and creativity in a wider context.

Interview with Cyril Helnwein

River Hunt: I thought a good place to start would be to talk about your experiences growing up, how you got to be aware of art, and how those experiences affected your own development as an artist?

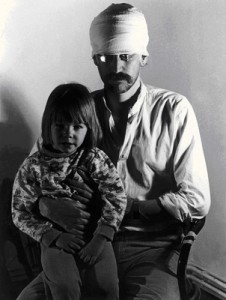

Cyril Helnwein: Well, most people would probably know who my dad is – Gottfried Helnwein, the world renowned painter who also does installations and stage-setting for operas and theatres (which involves everything from the costumes to the make-up, to the lighting of the stage too), so not only a painter as some people might think, but an all round artist. Growing up with him, I suppose you’re influenced whether or not you like it, because you’re exposed to it every day. I remember running around the place as a little kid, he’d be there painting and I’d come over, and sit on his lap and watch him paint. At that time he was mainly doing watercolours and they’re not as big as his paintings are now- some of the paintings he does now are like 20-foot wide paintings, these watercolours were maybe like 3-feet by 2-feet, so I was able to sit on his lap and be there with him painting. He would listen to the Rolling Stones very loud and paint away, and I would run around and watch him doing what he’s doing, you know.

RH: Being involved in the process of creating art at that age, must have really had a great impression on you, its no wonder you’ve become a photographer…

CH: Yeah, my younger sister is an artist herself, she does drawings mainly and she’s also a writer, (she’s had a book published by Simon & Schuster a few years ago, her first novel). And my younger brother is a composer, he does film music and he has his own orchestra; so we all somehow ended up as creative people of some sort.

RH: Isn’t it interesting how you all picked up a different part of the creative industry, you’ve got a musician, a photographer, an artist. I mean how did that come about, was that just random?

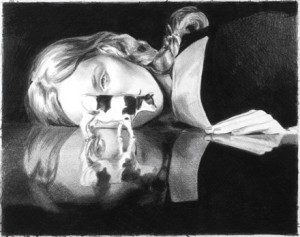

Mercedes Helnwein, “Cow with Reflection”, Black Pencil on Paper, 2008

Ali Helnwein Conducting Traction Ave Chambre Orchestra

CH: I don’t know how that came about; we all just picked whatever we enjoyed the most. My brother bought himself a violin when he was around 8 years old, and it was the most dreadful thing you could listen to back them, but now he’s a great violinist and composes his own classical pieces, and writes great scores. My sister has been drawing her whole life, ever since she was a little girl – she would be doing little sketches of princesses and ballerinas, and I guess never lost that. For me, I bloomed very late, in the sense that I never really took photography very seriously until I was in my early twenties. I’d always played around with it before, but I’d never really thought ‘ok this is what I’m going to do’, or ‘this is what I want to do’. I just developed, I suppose, late.

RH: How did you really get interested in photography?

CH: I don’t know how exactly, I kind of stumbled on it. I had a Yashica camera – which is a Japanese camera as you can probably guess by the name – that would allow me to take two photos on one frame, so by putting in a roll of twenty-four film, I’d get forty-eight, in other words I could snap away twice as much. I’d take pictures of birds, my dogs, my friends, anything around me, and I guess I just picked up a knack for it. Like I said, I never really put my attention onto that or really tried to hone my skills until I first moved to Ireland, that’s actually when it happened. I presume it had something to do with the fact that the landscape here is so beautiful and that the people here are so friendly – it’s such a bizarre little island, and my camera was always by my side at that time.

“Slievenamon”, photograph by Cyril Helnwein

RH: Do you ever use any other artistic mediums, or is it just photography for you?

CH: I can’t paint or draw at all; I mean I’m dreadful, can’t even do a straight line without a ruler.

RH: You must have a good eye for colour, form and lighting…

CH: I never really think of it like that, I just say, “I like it” or “don’t like it”. I don’t really pay too much attention to the mechanics, it just kind of happens. I exhibited “The Witching Hour” in Dublin, and I remember this kid coming in and explaining it to his parents. He didn’t know who I was, and I didn’t know who they were, but I was standing behind them in earshot. He was explaining in detail to the parents how I created this image using various layers in Photoshop, various channels and paths, and all these things I have no idea how to do. What that brings me back to – when I went out to shoot that, I kind of just had an idea that I wanted to capture a flying witch, and I drove up to this location in the Angeles Crest Forest, which overlooks Los Angeles, and I just thought “here’s a good wall, here the girl can jump”. I had the costume and the broom and all that of course, so it just happened, and it actually looks like she is flying. I think I managed to snap 10 pictures, before somebody came along and told us to shoo-off, so it wasn’t like I was up there for 3 hour trying various things.

“The Witching Hour”, photograph by Cyril Helnwein

RH: I think that many people would look at that image and just make the assumption that it’s been photo-edited…

CH: I don’t know how to do most of the Photoshop stuff, so that’s why I’m not doing it, I suppose. But I also don’t have any interest in it, that’s all. There’s nothing wrong with it – if they’re the tools that they use, then that’s what they use, but I do think there is a big difference between photography and something so manipulated that it’s really digital art.

RH: You’ve lived in a variety of places, Austria, Germany and Scotland and at the moment you’re living between Ireland and Los Angeles, how have those cultural and geographical changes informed and influenced your work?

CH: My parents were always moving, my brother and sister went to boarding school in England, and I have lived all over the world pretty much. So as a family we were always a bit like a tribe of gypsies without a home, always being somewhere but without ever settling, always the caravan outside ready to go. But when we came to Ireland it was the first time I felt a connection to the people and to the country itself. I don’t know how else to explain it, but I arrived here and I knew right away that this was where I was at home.

“Bun Mahon”, photograph by Cyril Helnwein

RH: How would you say that has carried through to your artwork? You said you were inspired by the landscapes and the history in Ireland, with so much experience of living in different parts of the world; that has to rub off on your work…

CH: Yeah, there’s such a big difference between Ireland and Los Angeles, they’re like different worlds almost. The fact is that when you’re stuck in one place and you can’t get out of it, or constantly surrounded by the same thing, you’re never going to have the chance to know what else is out there. I want to see other worlds, I want to travel, experience. I want to live life, whether it’s fun or not.

RH: I think it’s really important to experience new things, and allow those experiences to seep into your consciousness and unconsciousness, and let them come out in a variety of ways in your artistic output. Now, I was really interested to know what artists have had an influence on your photography… Who has been an inspiration to you in photography?

CH: Well obviously my father again, that’s where it all started – growing up with his influence just by presence. If I had grown up with a family of office workers and postmen, then who knows who I might have turned out to be! Some people say that it’s genetic, but I don’t think it has anything to do with that. I think it has more to do with the spiritual world, more than the fact that something’s in your blood, literally.

RH: If children grow up around other artists, if their parents are artists and get them involved in creative activities when there younger, they tend to believe they are good at it, and want to continue doing it. Whereas kids, who don’t get the opportunity, never find out that they’re good at it and creative. My belief is that everyone has the potential to be creative and do amazing things, but they don’t really ever really believe in themselves enough to try.

CH: Yeah that’s true. Kids, especially at the young age when they need a lot of support, should be encouraged and left to do what they want. A lot of parents try to limit their kids, “don’t do this, don’t do that, don’t go over there, and don’t touch that”. There is a big difference between keeping them safe and encouraging them to blossom to their full potential.

Cyril’s daughter, Croí Sequoia at age 2 ½, at work in her grandfather’s studio

RH: Children have amazing imaginations, they can invent a game out of nothing and it can be the best game ever, that’s really art in itself.

CH: Nowadays, with TV and X-Boxes and so on, imagination seems like a declining fad, compared to the days of when you had to imagine that your stick was a gun… now you actually just get to shoot people on the X-Box, which is also fun of course!

RH: I don’t know if you’re much of a reader, are there any particular authors that have really been an influence to you?

CH: I love to read, but I prefer to watch movies and let someone do all the work for me, so I don’t have to imagine anything! One of my favourite books is ‘The Old Man and the Sea’ by Ernest Hemingway.

RH: It’s really interesting you mention that, it’s actually one of my all-time favourite books and I sort of stumbled upon that by accident…

CH: Yeah, great book… I also love anything by Bukowski, Bulgakov’s “The Master and Margarita” is also a favourite of mine, and Jack London’s adventure stories – you can get lost in those books, and that’s what I enjoy. I like reading science fiction sometimes too; I don’t read romantic novels, ever…

RH: I wanted to talk a little bit about your photography, and in particular some of the series that you’ve produced. The ‘Ethereal’ series, by definition has this wonderful ghost like, spiritual quality, almost timeless. Was that influenced specifically by your move to Ireland?

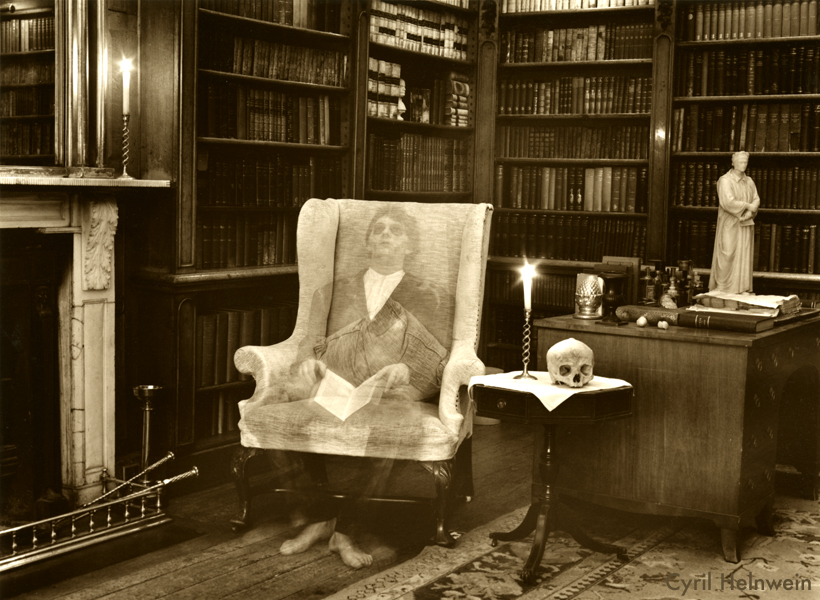

CH: Well, I suppose living in a castle in the countryside did help with the timelessness of things, and having that old-school effect! As photography goes, I personally enjoy the black and white; almost film noir approach, lots of heavy shadows, stuff like that. Coming to Ireland and living here all this time definitely influenced that. The idea from that series actually was inspired by a friend, he was doing a photography course somewhere in LA I think, he’d taken this picture of himself sitting on the street under a lamp post, with a long shutter speed, the same technique I then used for these photos. “That’s really neat” I thought, I mean it’s nothing knew of course as a technique, but when I saw his photograph I thought well I want to do something like that. His was very different though, I wanted to actually make a whole themed series out of it, and create this different world or this twilight zone.

“Nutrimentum Spiritus” (Lat. Food for the Soul), photograph by Cyril Helnwein

RH: One of the unifying features of that series is the Sepia colour tone, and that really contributes to the feeling of history and time and gives the images a sense of warmth, is that something you’ve preferred to do, to work in that colour range?

CH: Black and white photography is just that – black and white. In the darkroom you can tone it with sepia, or you can make it whatever- bluish tones, greenish, etc. The toning for the “Ethereal” series is actually not sepia but it’s very similar. Sepia is, I suppose, a generic brand like ‘Hoover to vacuum’ you know. This toner was actually hand-mixed, so every time you print one it would have to be re-mixed again, you can’t just buy it off-the-shelf like sepia. The toning definitely gives it a bit of warmth; it helped to create a more magical look to it, and it emphasises the old traditional sense of photography more in the sense that it’s not explosive brilliant colours everywhere. For the purposes of this series, it was really what I had to do to give it that kind of vintage, old-fashioned look.

RH: I think the images really work well as a series, and I’ve certainly enjoyed looking through them. Was it shot entirely in Ireland, in and around your home?

CH: I met my wife shooting that series actually… The series was shot in and around the castle as you can probably see from some of the locations. One is by the grand piano, one was shot in our library and one was shot in our wine cellar / “dungeon”.

RH: There’s an image in there with some lanterns at the top and two figures at the base of it…

“Love’s Tragic End”, photograph by Cyril Helnwein

CH: That’s the only one that was shot in Los Angeles actually, and there’s little story behind that. When I went to the lab to start printing and preparing the exhibition, I really only had 14 that I was absolutely happy with. When you exhibit in a room, you have to make sure it doesn’t look too empty, but also that it doesn’t look too full. But 14 for that space was a little sparse, so I said one more roll of film would have to be shot. Where I was living in Los Angeles at the time, in Downtown LA, they have a lot of that Art Deco architecture from the 20’s, and that location is actually one of the bridges that cross the LA River. Some might be familiar with it from the scene in “Terminator” where Arnold Schwarzenegger is driving his Harley Davidson through this narrow concrete river. I just shot that to have something to fill out the room better, but at the opening it actually ended up being the best seller and everybody loved it, which for me was like …err ok it’s not bad.

RH: There’s an image of these really old trees, I believe that’s Kojii standing by the trees. I really appreciated that kind of ‘Lord of the Rings’ moment…what with the old wood…

CH: Those are actually redwoods, we have an old arboretum at our property in Ireland that has some giant redwoods. I don’t know how old they are, but I’d say hundreds of years, similar to the sequoia trees in Western United States.

“Lady in the Woods” Photograph by Cyril Helnwein

RH: Moving on from that, the next series was ‘Myths & Fairytales’, now when I saw that, it brought back memories of childhood and people reading those stories. What was it about that subject matter that interested you?

CH: It was around the time my daughter had just been born. When I grew up, my father would always read me the old Grimm’s fairytales and stuff like that. He’s a great storyteller, so for me as a little kid it was always quite a visual thing, even though most of the time he’d just tell me the story without the book. I’d imagine all these crazy things in my head; it was very imaginative. Some of them are quite gruesome and tragic stories, you know.

RH: They’re quite a diverse range actually; One of the images that stands out for me is ‘Snow White and the Poison Apple’, which has this really beautiful composition and use of colour, then compare that to an image like ‘The Assassination of Humpty Dumpty’ which is such a great image, it literally made me smile when I saw that, and whenever I think about it, it brings a big smile to my face…

CH: That’s a very funny one for me as well… it’s one of my favourites.

RH: Did you enjoy the challenge and freedom of creating such a diverse and visually stimulating collection of images?

CH: With the Fairytales I could have gone on for the rest of my life, but I had to stop at some point. It was a lot of fun for me to shoot. I think you’ll notice also with the series I’m working on now, when that comes out… with every kind of theme or series I work on, I try to do something totally new, more for myself than anything else because I like to not get stuck in a rut, or be forced to always do the same thing. I can imagine Bob Dylan is pretty sick of singing the same songs for forty years now. I don’t want to end up like that as a photographer. I like to throw it all away and start new, and maybe come up with something interesting along the way.

“Snow White and the Poison Apple”, photograph by Cyril Helnwein

RH: That brings us on nicely to your latest series, which is the ‘Downtown’ series. For me that was a really interesting series. It’s much darker than ‘Myths & Fairytales’, and exudes a certain eroticism, there are some interesting juxtapositions of props, there’s a lot going on there, it’s really a feast for the eyes if you like.

CH: Exactly – rather than trying to tell a specific story (as with the Fairytales), I just let the person make up their own story for the picture, you know. Almost like having a chat with somebody but through the photograph, in the sense that they have to tell you what they’re seeing, as opposed to you telling them what they should be seeing. I suppose that there is a bit of, like you said yourself, a bit of eroticism in it, but it was not my intention to make something that would come across as erotic or turn someone on sexually. I like beautiful women, and also like black and white photography! I started off with B&W photography, so I brought it back to that again. The ‘Myths & Fairytales’ was very colourful and very explosive in a lot of senses, so I wanted to go back to where I started. Instead of setting up all these lights and different angles and stuff, all these props and costumes, I just wanted to use what was available to me. I shot the whole series at night only with ambient light – the light from the street lamps, from signs, from the glow of the Los Angeles smog, you know. We never got hassle from anybody; just a few people drive by, usually like “Woooo show us your tits!” One time actually, (for the shoot of the girl with the whip, lashing at the girl with the bunny ears and the walker), the police came cruising around the corner. My lookout… I always had a lookout with me, this time actually failed. Just as they were coming around the corner, he said, “Oh by the way, the cops are here”. But they were very nice once I told them what I was doing and kind of a bit disappointed they weren’t going get to see more flesh. They just said, “Mind yourself and be safe” and took off.

RH: You mentioned ambient lighting, was that something you specifically wanted to explore, or did it just come about due to the nature of what you were shooting?

CH: More due to the nature of what I was doing because it would have been impossible to shoot something like this with loads of lights to set up, and where in the middle of the street at night in Downtown LA do you find somewhere you can get power? I could have shot with battery packs or generators and huge lights, but that would have attracted too much attention, and would have given a totally different feel to the pictures too, I’m sure.

RH: I noticed in that series, one of the images, with the lady and the chain, it’s a diptych actually, how did that come about, and is that something you’ll look to explore more. I think in ‘Myths & Fairytales’ there’s a triptych, do you like working in that format?

CH: The triptych in “Myths & Fairytales” is the “Three Little Pigs”, so there are three parts. I could have shot all three pigs in one photo but for me it was more interesting to do each pig separately. In the case of this one, the diptych, I only came upon the idea when the film came back from the lab developed, and I was holding two of them up against the light, ‘wow they actually kind of match’ when I flipped one around, you know. But they weren’t perfectly matched because I had moved the camera around a bit, so I actually had to reshoot it. This time I went for the specific purpose of getting everything to line up perfectly, so I didn’t move the camera at all, and I made sure the model was in the right places, so they’d match up and create this kind of tug-of-war with the chain. That’s where the idea came from. The first time looking at the film with one backwards accidentally, I was like ‘wow that’s interesting’ and I just went with it.

“4th Street Bridge Tug-of-War”, diptych, photograph by Cyril Helnwein

RH: Isn’t it interesting how these things can come about by accident, and for me, I really like those images…

CH: Yeah, for me they’re probably my favourite images out of the series. The girl in it is not a model at all actually – she’s a school friend of my younger brother, and she was at first very shy about it all, but as you can see yourself she has an amazing body and could easily be a lingerie model if she wanted to.

RH: You’ve held a number of very successful exhibitions in LA, the most recent being in April this year. Maybe you could tell us a little bit about your experiences exhibiting and dealing with so many people, I know it’s been crazy having a lot of people down there…

CH: For that exhibition I purposely made sure there weren’t too many people because at past exhibitions I’ve held, it’s been almost too crowded – to the point where people can’t enjoy the artwork anymore. So for this one I wanted to make sure that it was a little more low-key in the sense of less celebrity hype, and more about the artwork, you know. To set-up an exhibition, there’s months and months of planning ahead – getting it all printed, getting it framed, finding the space, finding the gallery, the host and sponsors, etc. Personally, I haven’t had so many good experiences dealing with gallerists or art dealers. I’m sure there are great ones out there, but for some reason the ones that I’ve met have either been flakes or criminals in a sense almost, because they charge 50 or 60 percent sometimes and then don’t really do much work to sell stuff. And in the end, the majority of the sales you end up doing are your own clients anyway. So starting off as an artist, I recommend to most not to bother going with some fancy gallery that promises you everything but then doesn’t actually deliver anything, you know, unless they have a very proven track record with sales and a big collector base. But back to the question- there’s a lot of preparatory work that goes into it, and I’m lucky to have a wide circle of good friends, some of which are somewhat influential. So I would rent a space maybe for a week or whatever and have the exhibition there, and in exchange I would give the host or the person letting me use their gallery some artwork. Sort of like the barter system I suppose.

Cyril Helnwein, Marilyn Manson and Gottfried Helnwein at “The Ethereal” opening, March 2005

RH: How long were you on for, was it just the one night, you said you had the gallery for the maybe a week, how does that work?

CH: The ‘Downtown’ series I had up for a whole month actually, but we had a pre-opening “preview night”, then the actual opening night and then a closing night. But throughout the month, if someone wanted to come in, they could set-up an appointment.

RH: That’s a really nice way of doing it, it’s not as rushed. A lot of galleries will rent the space out for 2-3 hours to have an exhibition. That’s crazy.

CH: Yeah, I mean most people are 2-3 hours late anyway, especially in LA.

RH: Now I want to get back to something we touched on a little earlier, and that was around the use of Photoshop and digital image manipulation in general. Now you stated that the vast majority of your work is Photoshop free, why’s that important to you, and do you think that digital manipulation is diluting and devaluing the art form of photography?

CH: Nowadays, anyone with a bit of money can buy a digital camera and say “I’m now a photographer”. That’s all fair and I’ve nothing against people doing that, but for me personally when it comes to making photographs and I say making photographs instead of taking one, I like to set it all up have the props there, set the lighting, do everything right from the beginning so I don’t have to later in Photoshop, maybe cut something from one photograph and paste it into the other, or something similarly as drastic as that. The one thing I will do in Photoshop is slight colour balance or tonal curve adjustments, stuff that if you were working in a lab you could do with film. You can adjust the contrast when you print something in the lab, by varying the amounts of time exposed to a chemical or whatever, and you can actually dodge and burn stuff by holding a piece of cardboard over a spot, thus over-exposing the uncovered area and burning it out. So when I say 99% of my work is Photoshop free, I mean in the sense that I do some very slight adjustments like that, but everything else you see is as it was taken. So far, most of it is shot on film anyway.

RH: I mean if we look again as something like the ‘Assassination of Humpty Dumpty’, that’s a photograph of timing really, and some people might not appreciate the effort that’s gone into achieving that…

“Assassination of Humpty Dumpty”, photograph by Cyril Helnwein

CH: I had to shoot like 40 eggs to get the timing right on that! It was quite funny actually because, you know, everyone has seen the photograph of the bullet going through an apple, and I wanted to do something like that with ‘Humpty Dumpty’. An actual bullet from a real gun would… you could never capture that time-wise by hand – you’d have to set up a sound trigger so that when the gun goes off it triggers the camera. So it’s literally milliseconds. I didn’t want to use a real gun, as I was just a bit too lazy to set all that up. I just bought a whole lot of eggs and I had a spring-loaded bb gun. My friend had the gun and aimed it at Humpty Dumpty, and I would say ‘3-2-1-Go!’ and we tried to fire our “weapons” at the same time. Some photos I’d catch it before it would hit, some after where it was too messy and you couldn’t see much of the face anymore, so we had to go to around 40 eggs to be able to say there’s definitely 1 or 2 that will work.

RH: Well I certainly admire your patience.

CH: We had Omelette for the next week!

RH: Let’s move onto art and creativity in a wider context. What does it mean to you to be an artist, and do you feel any responsibility to society in that role?

CH: I don’t really consider myself an artist. I do it because it’s fun, I wouldn’t do it because I feel I have an artistic responsibility to society or something presumptuous like that. At the same time, so far most of the subject matter that I’ve touched on is not really political, not racial… I don’t know, they’re kind of more innocent I guess. I suppose an artist does have a responsibility in a sense of keeping earth happy, you know, letting people escape to somewhere there imagination is in control, as opposed to where their 9-5 job or life’s problems are pressuring them. I suppose in that sense, art is very, very important. If you took history over the last hundred years even, and took everything away that was art, it would be a pretty bleak, dark and miserable place. All that would be left is insanity, war and destruction.

RH: In terms of the creative process, what fires your imagination? For a lot of people they’ll have a specific media type, whether that be reading a book, or listening to music or watching a movie as you said earlier. Is there anything particular for you that really works?

CH: No, there’s not a specific thing that gets me fired up or gets my imagination going. I don’t try to pressure or force myself.

RH: I guess surrounding yourself in a great environment…

CH: Yeah, being surrounded by other artists all the time, watching great movies, even having interesting chats with friends and with family, it all helps to keep your mind imaginative.

RH: If you look around in today’s society, it’s increasingly saturated with imagery from adverts, pop-ups, magazine articles and reality TV, as a visual artist how do you contend with that, and is it something that concerns you?

CH: I guess kids today have less chance to build an imagination of their own because they are constantly bombarded by imagery and different mixed messages. It seems to me a lot of kids that don’t have much cultural influence just end up watching TV, and they start becoming these characters that they see, you know. They either have to be a goth, prep or whatever the different stereotypes are. With the fact that TV is such a huge thing now- every western household has at least one, even when you watch just one programme you’ll have 20 interruptions in that. You can’t actually just watch the programme; you get interrupted every 5 minutes with a commercial. I think that can be quite harmful, because first of all you’re not contributing anything, it’s only coming to you, it’s only in-flow and at the same time that flow or message towards you is being chopped, chopped, chopped. No wonder some people can’t focus or concentrate anymore. And it doesn’t surprise me that there’s a rise in teenage crime and things like that.

RH: There’s so much visual entertainment these days, whereas in the past, you’d come across an image that’s controversial or that’s doing something new and it would excite you, and you could look it and really be wowed by it, but now, with so many billions of images, I almost wonder if it waters down that experience.

CH: Well yeah, I suppose there is a certain numbing of the senses, you know, but what can you do? For me as a photographer I just do what I like to do and I don’t break my head wondering how it will compete with something else.

RH: It’s almost like kids these days will look at an image and will expect to see the adverts around it, and expect the distractions. If you go to a gallery to see artwork first hand, then you get that experience of just viewing a photograph one-on-one, and to be fair, something that kids these days are not used too.

CH: Yeah, I suppose not, and like you said yourself, when you’re actually viewing artwork as it’s meant to be viewed – in person at a museum or at a gallery, then there’s only a communication between the artwork and yourself, and there’s nothing of someone trying to sell you the latest candy, or the new cell-phone. Seeing an artwork in person is definitely a much better experience than looking at something over the Internet or the TV because there’s so much detail and colour loss just because it’s now digitised and this small as opposed to a 4-foot painting.

RH: Take an abstract work like a Rothko, there’s a room dedicated to his artwork at Tate Modern. Now most peoples experience of his artwork is of this decorative art, they’re looking at a 30-centimetre reproduction. It’s so far removed from the vastness and overall dark experience of viewing his actual work at the Tate, it’s really quite sad. I’d certainly encourage people to get out there and view the work first-hand.

CH: That’s the other part of the art-world – whether or not you’re successful has nothing to do with ‘are you a good artist, or are you a crap artist’, but ‘do you know how to market yourself, or do you have someone who knows how to market you’ and unfortunately marketing or publicity is practically the only thing makes you successful, no matter if you are any good, or if you’re work has any meaning to it. When you go into a gallery – the National Portrait Gallery in London for example is a great place to see, when you walk in there you just see these big paintings, and you’ve seen them before in books maybe or on the Internet but seeing them in person, that’s when you really get the connection, and that’s what art is supposed to be – it’s a communication you know, it’s suppose to make you feel something, inspire you, open your eyes.

RH: The Internet has really changed the way people interact with media, people will be going onto the website and viewing your work, and for kids it’s maybe the only way they’ve ever experienced artwork, what do you make of this digital encounter with art?

CH: I don’t think there’s anything wrong with it necessarily. If we go back to times before the Internet, some kids would have never been exposed to much art. At least now they’re getting more over the Internet, even if a lot of it is rubbish, so in that sense it’s definitely something positive. And who knows, maybe in 10-years time you’ll be able to do a virtual museum tour with some kind of gadget on your head, where you get everything. When I grew up in Vienna, we lived a 10-minute walk to the Natural History Museum and to the Art History Museum. As a 5 year-old boy, I’d come home from school, and these museums was the first place I’d go, and I’d hang out there almost every day. The Natural History Museum was my favourite place because there was room, after room, after room of stuffed bears and tigers, crocodiles and anything you can imagine. They would change their smaller exhibit maybe once a year, but the basic exhibit would always be the same. It was almost like my second home at the time. I remember they showed the “Jungle Book” Disney movie, I think I watched that movie at least 400 times, and I can still watch it today with my daughter and enjoy it.

Natural History Museum, Vienna – photograph by Matthias-Kabel

RH: Like you say the Internet improves the accessibility of the work, but I do hope people follow through and go and see the work in person.

CH: Every person is a different person, and to have one person not interested is totally fine. Some people like some artwork, and some people hate it, but art is a very personal thing, and it should have no influence on you if someone else likes it or not.

RH: What advice would you give to youngsters that are just starting out in the creative arts, and as you’ve got a daughter yourself, how do you get them interested in art?

CH: I would say to anybody that wants to be an artist, ‘go for it!’ there’s nothing holding you back except for yourself. It’s definitely tough sometimes, because you don’t have your daily income, as you would if you were working as an accountant or whatever, but I could never imagine myself as an accountant. I would just fail completely and commit suicide on the first day. My daughter draws and paints every day, sometimes she’ll be painting with my father in his studio – she has her little canvas set up next to his big canvas, and he’ll be there doing brushstrokes up and down, and she’ll kind of out the corner of her eye, look at him and do the same brush strokes. You can tell she puts a lot of thought into it too, not just random brush strokes or colours somewhere on the canvas.

RH: Have there been any disasters with her working on the wrong canvas?

CH: My dad’s actually very lenient, he’ll let her paint something over his painting and he’ll have to quickly wipe it off before it dries. There’s actually one painting- I can’t remember which one now, it’s from the “Disasters Of War” series, where you’ll see a bit of a pink hue in one corner – I guess he never managed to fully over-paint that area. And I just recently came across a painting of his from the early 80’s and noticed what could almost look like a signature on it, but not his, it was like a kids scrawling and it was what looked like Russian letters, (the Cyrillic alphabet), and I asked my mum, ‘what the hell is this, did Croí get at this or something and where did she learn to write Russian’ and then she said ‘No, that was you when you were a kid’. I’d forgotten about it, but I’d actually signed my name on his painting in Russian.

RH: Ok, a bit of a random question for you… if we were going to make a movie about a day in your life, what would the basic plotline be? You said you like movies so this one should be good for you…

“Castle at Dawn”, Photograph by Cyril Helnwein

CH: Well it’s hard to say because every day is so different from one to the next. I might one day be mowing the lawns, or hanging off the turrets to clean out the gutters of the castle, or if I’m in L.A it’s a totally different thing again, you know. On a weekend I might have a bit of time to take my bike out for a spin on the Pacific Coast Highway, or I might be driving my dad’s paintings up to San Francisco for an exhibition, or last year I had to fly to Prague to set up an exhibition for him there. Because I do his technical studio work, like stretch his canvases onto frames, I package them for transports, set up his photo shoots, etc. So I’m very busy working for him on top of my own stuff. My days are so varied, but that’s how I like it – something new all the time.

RH: It sounds like you keep yourself busy at least…

CH: Very busy yeah, almost too busy.

RH: Do you find that you’ve achieved the right balance between work, art and your home-life?

CH: I’d like to have more time just to focus on the creative side of things, as I’m sure everyone would, and that’s where it gets tough – do you spend less focus on promotion and sales, and when do you get time to focus on creating some new stuff? But I haven’t got to the stage I want to be at yet; I’m far from there actually. But at the same time, I’d prefer not to be an overnight success like some things that are then forgotten the next day, you now, like some reality TV stars who have their 15 minutes of fame.

RH: You mentioned a little earlier about the new series that you’re working on, could you give us a little preview of what that’s going to be, and when it’s going to be around?

CH: I can’t say when it’s going to be out yet, because I don’t know when I’ll be done with it. I’ll know when I’m finished and I don’t know when that is until I’m there. I’m hoping some time early next year it should be finished and then depending on how soon I can find a gallery, a host to sponsor the event. What I’m working on now is a series strictly based on idioms and slang. It sounds a little weird, I know, but you’ll just have to wait until you see it I suppose! It’s mostly all colour, not black and white like my last series, and it’s more similar in a sense to the ‘Myths & Fairytales’ series, in that the shots are set-up with props and different things. It’s more a stage setting, as opposed to capturing something organic that’s happening.

RH: Well I’ll certainly look out for that, and maybe when you’re ready to release that, we can hook up again and have a chat in a little more detail about it.

CH: Yeah, definitely…

RH: It’s been amazing talking to you today, thanks for taking the time out for this interview. You’ve been a true gent, so thank you.

CH: Thank you!

Further Resources:

You can connect with both River Hunt and Cyril Helnwein using the links below:

RIVER HUNT

River Hunt Art Blog – https://www.riverhunt.org

Twitter – http://www.twitter.com/riverhunt

Facebook – http://www.facebook.com/riverhunt

CYRIL HELNWEIN

Cyril Helnwein Photography – http://www.cyrilhelnwein.com

Facebook – http://www.facebook.com/Cyril.Helnwein.Photography

Deviant Art – http://cyril-helnwein.deviantart.com

Twitter – http://www.twitter.com/cyrilhelnwein

Myspace – http://www.myspace.com/cyrilhelnwein